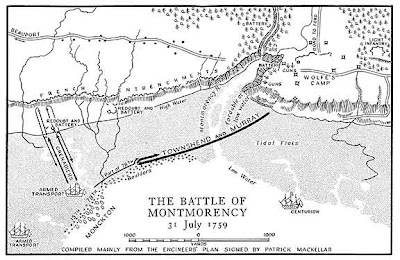

Tuesday, July 31, 1759 Another hot, sultry day, but there is a breeze; the ships can move. Wolfe launches his attack on the redoubt west of Montmorency Falls. Things go wrong immediately.

Tuesday, July 31, 1759 Another hot, sultry day, but there is a breeze; the ships can move. Wolfe launches his attack on the redoubt west of Montmorency Falls. Things go wrong immediately. Around low tide, near mid-day, two armed transports, Russell and Three Sisters, are deliberately run aground on the sandbanks adjacent to the redoubt. They are to provide close-range fire support for the attackers. But the distances are greater than Wolfe had guessed. Though the French on the heights can pour heavy fire on the helpless ships, the ships will be unable to assist the infantry.

Wolfe himself boards the Russell under heavy fire. He sees his whole plan is based on a misunderstanding. His objective has been an advanced redoubt close to the beach and outside the French defence line on the hilltop, but he now sees it lies much closer to the French entrenchments and gun batteries that he had judged. Even if the British seize the redoubt, they will be unable to hold it under French fire. Montcalm will have no reason to send troops down to engage the British around the redoubt – the whole point of Wolfe’s plan. He will just pound it and them to pieces.

Wolfe recasts his plan on the fly. Seeing the French in rapid motion behind their lines, Wolfe hopes this is confusion. He decides on the thing he had resolved to avoid: a frontal attack: past the redoubt, up the steep banks, and into the dug-in French lines. The grenadiers originally intended to seize and hold the redoubt are given this mission. Monckton’s troops will come in boats from Pointe de Levy to support them. So will Townshend’s troops, who will cross the Montmorency ford from their encampment east of it.

The grenadiers’ boats, delayed by shoals in the river, finally come ashore after 5 p.m. The French expediently abandon the redoubt and retreat to their entrenchments up the bank. But Monckton's and Townshend's forces are not yet there. Captain Knox describes what follows:

The troops to the eastward of the Fall were in motion to join and support the attack; but the grenadiers, impatient to acquire glory, would not wait for any reinforcements, but ran up the hill, and made many efforts, though not with the greatest regularity, to gain the summit, which they found less practicable than had been expected: in this situation they received a general discharge of musketry from the enemy's breastworks, which was continued without any return; our brave fellows nobly reserving their fire, until they could reach the top of the precipice, which was inconceivably steep; to persevere any longer they found now to little purpose; their ardour was checked by the repeated heavy fire of the enemy. As if conscious of their mistake, the natural consequence of their impetuosity, they retired in disorder (in spite of the most unparalleled valour and good conduct on the part of their officers) and took shelter in the redoubt and battery on the beach, where Brigadier Monckton's corps were now landed and formed; those under Brigadiers Townshend and Murray being also at hand, ready to sustain their friends.The retreat of the grenadiers coincides with what Knox describes as “the dreadfullest thunder-storm and fall of rain that can be conceived … the violence of the storm exceeded any description I can attempt to give of it.” Driving rain silences the flint-sparked black-powder muskets on both sides; if the defenders cannot fire, is one more desperate bayonet charge into the French lines possible? No, the streaming, slippery slope is impassible and the grenadiers have taken enough punishment.

Meanwhile, the rising tide will soon flood the ford. If they linger, the British may be trapped on the beach. Wolfe orders the redoubt abandoned and the Russell and Three Sisters burned where they lie. The brigadiers bring their men off in fairly good order, some in boats, some back across the ford. Knox counts the cost:

The loss of our forces this day, killed, wounded, and missing, including all ranks, amounted to four hundred and forty-three; among whom were two captains and two lieutenants slain on the spot; one colonel, six captains, nineteen lieutenants, and three ensigns wounded.

Map: from Google images, originally published in Stacey's Quebec 1759.